See more of my photos from this hike.

This article gives more details, and has directions to the trailhead.

Utah's west desert is an amazing paradox - an alien-looking land, forbidding yet starkly beautiful. It offers great hiking options and I enjoyed challenging one of its best summits last weekend.

We climbed Notch Peak, which rises some 5,185 feet above the surrounding desert. The peak's south side has a section that is sheer for about 2,200 feet - and that makes it a cliff of major magnitude.

El Capitan, the famous rock mass in Yosemite National Park, has a vertical rise of about 3,000 feet. As precipices go, Notch Peak is almost as impressive, if you combine its vertical and almost vertical sections, but Notch is virtually unknown because it is located in Utah's remote, desolate west desert.

From the top of Notch, looking almost straight down for most of a mile, the feeling is overwhelming. Vertigo is common as you move toward the edge. It sometimes feels like a mysterious force is sucking you toward the cliff. Hikers innately respect the mountain; most lie on their bellies as they peer over the edge.

Most of the towering cliffs in Zion Park drop a meager 1,500 to 2,000 feet straight down. Aside from Notch and the Yosemite peaks, I don't know of another precipice in the US that boasts such an impressive sheer face.

I've wanted to hike Notch for some time, and finally made the trip last weekend. It was a great experience, well worth the effort.

Notch Peak is located west of Delta, about 3.5 hours from Salt Lake City. The hike is moderately strenuous, about 8 miles round trip. We made it up and down in about 5 hours, and that allowed time to play on top.

There is no formally designated trail and you need route-finding skills to make this hike. A topo map is essential and a GPS comes in handy.

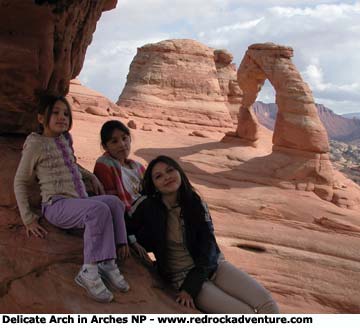

We approached from the east and followed a winding canyon up to a saddle just below the summit. Hiking in the canyon is relatively easy but you do have to bust through some brush and climb around one dryfall. You also ascend a series of ledges, almost stone steps. Hiking through the canyon is fun and moderately adventurous. We had a couple kids with us, ages 12 and 13, and they made it with no problem.

As you come out of the canyon onto the open ridge, you gain a panoramic view of the surrounding desert. You feel like you've been transported to some distant planet, with alien-looking landscape falling away in front of you. The surrounding desert is mostly flat and devoid of life. The glassy waters of Sevier Dry Lake reflect distant brown mountains, with snowcapped mountain peaks visible in the far distance.

You look out over hundreds of miles of desolate country, no cities or towns in sight, a few roads the only signs that humans have impacted this vast land.

Views from half-way up the mountain are impressive and the wonderment grows with each step as you approach the summit.

The final push to the saddle is steep and exhausting, even if you are in good shape. You hike over small, loose pieces of broken shale and that makes for poor footing. This section of the hike is short but more difficult than it looks.

When you reach the saddle just below the peak, the summit rises a couple hundred feet above you to the left. To the right, we followed the ridgeline to another saddle, a little lower, where we were able to take photos that captured most of the peak's dramatic rise.

Bristlecone pine trees grow in a grove adjacent to this second vantage point. They are amazing trees, some thousands of years old. Gnarled and scarred, bristlecones are the oldest living things on earth. Some, on nearby Wheeler Peak, are thought to be more than 4,000 years old.

For something to live for thousands of years, you would think it must grow in the best soil, in a spot where temperatures and other conditions are favorable. Not so. These trees push their roots down into cracks in the rock, where there is little soil available, and the soil that is available is poor. They grow at high altitudes, here about 9,200 feet, on windswept slopes where summer days are very hot and winter nights are bitter cold.

The grove on notch is impressive.

Notch Peak makes a great hike - perhaps the best in the west desert. One of the best in Utah.

- Dave Webb

Hike details:

Notch Peak summit elevation: 9,655 feet

Sevier Dry Lake elevation: 4526 feet

Sawtooth Canyon Trailhead

39.128, -113.364

Canyon Fork

We hiked up Sawtooth for a short distance to a fork; at the fork we went left and stayed in the canyon until we were right under the saddle.

39.1334, -113.373

Saddle below summit

39.1426, -113.406

Notch Peak

39.1427, -113.409

Bristlecone Grove

39.1433, -113.403

An AP news article about the sale of oil and gas leases near Utah national parks is being widely published, and is causing a bit of uproar. The sale is controversial and should be examined. Unfortunately, the AP article includes several misstatements, some so distorted they reek of sensationalism.

An AP news article about the sale of oil and gas leases near Utah national parks is being widely published, and is causing a bit of uproar. The sale is controversial and should be examined. Unfortunately, the AP article includes several misstatements, some so distorted they reek of sensationalism.